Queer Mr. Lincoln in the K-12 Classroom

On the shelf of Abraham Lincoln books in my office, nestled between old black and white anonymous photographs of tourists posing by statues of the Great Emancipator, there is this homemade note written in the adorably sloppy hand of a 7-year-old: “Dr. Morris thank you for the interview. I just did my presentation. I learned a lot. ♥ Shaw.” In truth, I learned more from Shaw Miller on that day in 2008, and on one other in 2010, than he did from me—remarkably unsettling and inspiring encounters, from which this project emerged. To know more about my relationship with Shaw, you’ll have to read the essay.

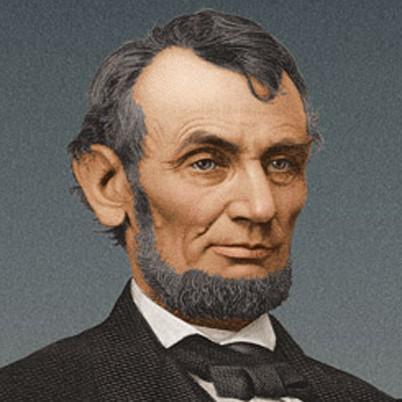

For more than a decade, I have been researching and writing about Abraham Lincoln’s sexuality. Trained in rhetorical criticism and public address, I self-identify as a queer archival critic, a critical rhetorician/scholar-activist who analyzes and deploys the past in its diverse presences and absences to contribute to GLBTQ worldmaking—a safer, more habitable, healthier, more just, more equitable, more intersectional, more peaceable, freer, more fulfilling, happier world for all GLBTQ people, wherever they may be.

Insinuations about Lincoln’s non-normative sexuality have circulated since the early 20th century, perhaps always, becoming more visible as part of gay liberation and pride discourse and performance in the 1970s and 1980s. Claiming of Lincoln as a “great gay in history” didn’t seem to gain much mainstream notice until expanding and magnifying GLBTQ presence in law, politics, and popular culture made it an issue, perhaps even a threat to national memory and identity. From a very early age, after all, inevitably and ineluctably, American children learn that Lincoln is who we are, whom we should aspire to be, and those normative ideas and feelings across generations in ways large and small are reaffirmed and, when necessary, defended.

As a lifelong public speaker and professional rhetorical critic, I have always admired Lincoln, and as a gay man, the question of Lincoln’s homosexuality intrigued me. As a scholar I have been much more interested in the rhetorical, cultural, and political dimensions of the Lincoln Enclave, those seeking to prove Lincoln’s homosexuality, and of the Lincoln Establishment, those invested in preserving his heteronormative legacy. A project in public address and public memory, my earlier work taught me much about Lincoln’s vexing and propulsive biographical and textual ambiguities, the multifaceted power of his afterlives, and about the politics of evidence and erasure. The question, if not the struggle, I concluded, would never be resolved because Lincoln’s life could not definitively be established as gay or straight—and in this indeterminacy, I came to believe, is Lincoln’s queer promise, which I sought to explore in “Sunder the Children: Abraham Lincoln’s Queer Rhetorical Pedagogy.”

Increasingly influenced by disciplinary discussions of “engaged scholarship,” and by way of asking “what next?” in this project, I wondered where beyond academic audiences and pop press stories queer Lincoln might go and what he might productively do. My experiences with Shaw led me to think about K-12 classrooms. I wondered whether queer public address and public memory work could be mobilized within, as a mode of, rhetorical education; whether speaking, composing, discussing, debating, and/or performing Abraham Lincoln in the classroom (which has been done for more than a century) in a non-normative way (which has rarely been done) could make a difference for GLBTQ children and youth, indeed for all students who would benefit from challenges to homophobia and heteronormativity in an age of bullying.

Immersing myself in educational theory and analysis related to GLBTQ issues, I discovered that while legal protections for being out in U.S. education hearteningly have expanded and deepened in recent years, actually speaking or teaching out at school could be another matter altogether. My own surprising discomfort, stammering, and silence when given the chance to discuss Lincoln’s sexuality with Shaw resonated here. My research led me to conclude that official protections commonly are rendered immaterial by the paralyzing homophobic effects of the longstanding discourse of “recruitment,” the disciplinary and scapegoating illogic that queers reproduce through molestation and brainwashing of children, that classrooms and lessons populated by queers are by nature predatory zones. In response, could queering Lincoln in the classroom serve as a rhetorical inducement that might set tongues wagging about sexuality, that might interrupt and challenge and open and affirm and transform students and teachers, their peers, colleagues, and families?

In exploring this possibility, I critically engaged and queered two K-12 texts and teaching resources by imagining GLBTQ content infused into them with the express purpose of speaking thus unsettling sexual and gender norms and their often violent consequences. The first, Looking at Lincoln, is a charmingly didactic homage written for 4-8 year olds by the brilliant children’s author, illustrator, and blogger Maira Kalman. I ventured not only to suggest ways in which Kalman’s book is already queer/hospitable; but also how one might (age-appropriately) reconfigure Lincoln’s non-normative sexuality within its pages: depicting Lincoln’s same-sex crushes and sleepovers; drawing gender and sexual justice lessons from Walt Whitman and Frida Kahlo.

In the second case, I queerly appropriated and recalibrated the high school exercises regarding Lincoln developed by education experts Sam Wineburg, Daisy Martin, and Chauncey Monte-Sano in their acclaimed book, Reading Like a Historian. At this advanced level, the rhetorical provocation and performance of queer Lincoln affords complex and (more) candid intersectional engagement and embodiment regarding sexuality. Students could scrutinize and mobilize (or reject) Lincoln’s corpus through archival materials (1807-present) to critically assess and imagine issues such as gay marriage, coming out and outing, the meaning of queer—personally, relationally, communally, nationally, globally.

Queer Lincoln rhetorical pedagogy of course is no panacea. Bullying of students and teachers will continue, and in any case the institutional and structural challenges inside and outside of U.S. schools are far larger than the media-hyped “epidemic” of bullying, all diminishing what any queer intervention might achieve. But Lincoln’s ubiquity, inertia, indeterminacy, eloquence, and—like it or not—queerness nevertheless hold promise for rhetorical inducement and invention in a site that, for myriad reasons, matters. This essay also encouraged me to query the applied possibilities of work by Rhetoric’s Lincolnists, as well as imagine collaborations and coalitions across educational and policy domains by all those, intuitively or explicitly, committed to GLBTQ worldmaking.