Lights, Camera, Detonation

The Cold War has not quite ended. The way the United Statescommunicates about terrorist threats today mirrors the way adversaries were depicted during the Cold War. The messages conveyed in government-produced films of atomic tests of that era emphasized the U.S.’s mastery of nuclear technology, primarily through the symbol of the competent nuclear operator at his console, which today is contrasted with images of the irrational and imbalanced terrorist. The Cold War imperative to communicate to the American public the superior technological competence of the U.S.has endured in the interactions between the West and non-state actors in the current ‘war on terrorism.’

Although it might seem a distant part of history, the legacy of the Cold War pervades global economics and politics. This is the era that birthed many of the institutions which support internationalgovernance and security today, such as the United Nations Security Council, International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank, and bequeathed technologies which we continue to depend on, such as supercomputers and the Internet. With this legacy has come another feature of the Cold War: the urge to construct the West as modern, civilized, and able to control ruinous technologies such as nuclear bombs, while presenting adversaries as incapable, irrational and dangerous. The idea is that the primitive and imbalanced nature of terrorists and their potential misuse of nuclear weapons make this technology dangerous, while in the right hands – rational, modern,Western hands— perfect control is possible.

In our article, we argue that stories of technological competence and incompetence divert attention away from the inherent danger of nuclear weaponry. . The logic of nuclear legitimacy was based on a fundamental belief in the technological integrity of nuclear weapons organizations, including laboratories, test sites, and assembly plants. This logic made it possible to rationalize the U.S.’s use of nuclear weapons based on its ability to track, control, and predict every facet of this technology.

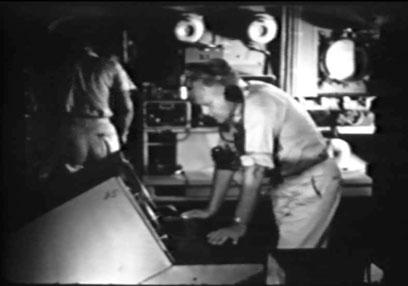

Central to this story was the image of the efficient and competent American nuclear operator at his console. Surrounded by indicator lights, gauges, switches, and buttons of countless sorts arrayed on a control panel, which he operated using knowledge unique to his profession, he represented a new kind of human in Cold War and post Cold War culture, one seemingly able to bring an uncontrollable device within the purview of human control. His control panel, the interface with the awe-inspiring weapons he controlled, was the physical embodiment of the screen of nuclear legitimacy, placing weapons at a safe distance and functioning as an important image of nuclear legitimacy. It is thus possible to study the iconic control panel the same way scholars have analyzed words printed on a page, faces captured in portraits and photographs, and public memories preserved in national monuments.

The control panel was a central part of the apparatus surrounding the bomb, and was created to scientifically measure the nature and scale of the bomb’s effects. The presence of such machines and equipment was also used to provide reassuring images of the U.S.’s technical ability to keep the bomb in check, although, paradoxically, the equipment was necessitated by the inadequacy of human perception. In the bomb, science had produced a technology that far outran the observational capacities of the human medium of sight, yet, state-sanctioned images and discourse continued to emphasize the role of the operator’s technological mastery as a way to assuage public anxieties about nuclear destruction.

Against the backdrop of President Dwight Eisenhower’s 1953 ‘Atoms for Peace’ address to the United Nations, the Eisenhower administration decided to release government-produced films of nuclear tests in an effort to be ‘candid’ with the world about the Bomb. A fundamental thrust of this propagandistic drive involved emphasizing the U.S.’s mastery of the bomb through films that depicted the Armed Forces’ superior command of nuclear technology and access to specialized equipment, control functions and skilled expertise.

At the center of this visual campaign lay Lookout Mountain Laboratory, a well-funded Air Force unit in Hollywood credited from 1946 to 1968 with some 6,500 films, most of which concerned atomic tests. The laboratory was “the only self-contained film studio in Hollywood,” employing “more than 250 producers, directors, and cameramen— all cleared to access top secret and restricted data and sworn to secrecy regarding activities at the studio.”

Lookout Mountain’s cinematic productions highlighted the Armed Forces’ ability to control the bomb through orderly processes, operational oversight and modern, technological competence. The films created and perpetuated a narrative of effortless control of the bomb and presented nuclear operators as a new expert class of labor to which viewers could aspire. Portrayals of the nuclear operator, handling the bomb ‘‘without strain,’’ diverted attention from the destructive scale of nuclear weaponry—which, after all, is and was at the core of moral objections to nuclear weaponry—and toward the elegance and efficiency of technological processes.

Atomic test films such as Operation Ivy and Operation Castle sought to make the bomb an object of rational control and aesthetic appreciation. The films feature Hollywood conventions such as musical soundtracks, stunning shots of natural scenery, and ample attention to the narrative drama of the ‘‘countdown.’’ At the same time, the nuclear operator is placed center stage, using his technical prowess to control vast machinery with “a simple flip of the wrist,” as Operation Ivy’s actor-narrator describes in admiration. In the process, viewers are distanced from actual questions of the bomb’s danger and the fact that these devices cannot in fact be fully controlled or comprehended.

In contrast to the modern nuclear operators stands the image of the U.S.’s adversaries as primitive and technologically incompetent. They have not reached the full level of technological control associated with nuclear legitimacy and are capable only of approximations of the level of technological sophistication and societal advancement achieved by the U.S. In this narrative, nuclear terrorists and rogue hold an “incomplete status” in relation to civilizational progress . These fractional foes cannot, it seems, ever pose a real threat to U.S. security, except as deranged, mad, or maniacal.

Assumptions of the incompetence of enemies rendered the events of September 11, 2001 particularly shocking because terrorists there gained control of technology presumed to be beyond their capabilities. The attempt to regain technical superiority in the eyes of the public is evident in CNN reports of alleged Al Qaeda documents detailing how to build conventional and nuclear weapons. In CNN’s report, produced in collaboration with the ISIS, the documents appeared to be askew and disheveled crude pencil drawings, suggesting a semi-primitive enemy using simple materials and equipment. Should terrorists actually gain access to nuclear weapons, the drawings suggested they would be unable to use them properly. In contrast, CBS coverage of security measures for Denver’s 2008 Democratic Party Convention emphasized law enforcement officials consulting their high technology interfaces, visible again in the face of a threat to the West’s status as nuclear moderns.

For terrorists to wield nuclear weapons means that they are capable of mirroring the West’s sophisticated nuclear structure and that they no longer exist in a separate sphere of nuclear illegitimacy. Hence, images of terrorists remain locked within a vocabulary of technological incompetence, primitiveness and irrationality. This frame is a remnant of the Cold War logic of legitimation that has lingered into the post Cold War world. This world views others as less than rational and thus less likely to have control over nuclear weapons, a view which rationalizes the West’s own enduring claim to nuclear hegemony.