Black Women’s Historical Speeches: Asserting Self-Determination and Challenging Racist Narratives

The 1893 World’s Congress of Representative Women (WCRW) occurred concurrently with the World’s Columbian Exposition. Although the WCRW was meant to portray women’s advances broadly, only a handful of Black women were invited to speak. In a new article published in NCA’s Quarterly Journal of Speech, Sara C. VanderHaagen argues that these speakers situated emancipation as the beginning of Black women’s progress in the United States. Furthermore, they emphasized that Black women’s progress must be understood in relationship to slavery and that they were their own agents of change. VanderHaagen shows how contemporary Black feminist thought can help us better understand these women’s speeches.

The 1893 World’s Congress of Representative Women

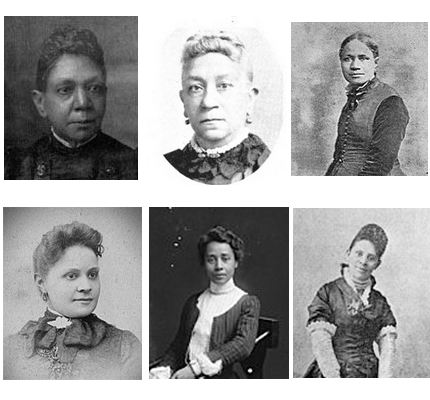

The WCRW was attended by 150,000 people and honored the quadricentennial of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. There were more than 500 speakers, but only six were Black women:

- Fannie B. Williams: Born into an affluent free family in New York, Williams was married to a Chicago journalist and was a well-recognized speaker.

- Anna J. Cooper: An educator and published essayist, Cooper was born into slavery and later graduated from Oberlin College.

- Fanny J. Coppin: After an aunt purchased Coppin’s freedom, Coppin graduated from Oberlin College and went on to work as a teacher, missionary, and African Methodist Episcopal church leader.

- Sarah J. W. Early: Born to free parents, Early was a teacher and temperance lecturer.

- Hallie Q. Brown: Born into a free family, Brown was a graduate of Wilberforce University, an educator, and a “charismatic public speaker.”

- Frances E. W. Harper: The most well-known of the speakers, Harper was born into a free family and was active in the abolition, women’s suffrage, and temperance movements.

VanderHaagen examines these women’s speeches both as individual speech acts and as a broader, collective conversation among the speakers that illuminates Black women’s activism during this period. VanderHaagen argues that this is consistent with “Black feminist thought’s emphasis on the communal features of Black women’s resistance.”

Emancipation as the Beginning of Black Women’s Progress

In their speeches, the women argued that emancipation was the “starting point for their accounts of progress.” By making this argument, they were rejecting the story told by the World’s Columbian Exposition, which depicted white colonialism as the harbinger of “progress” and treated Columbus’s arrival in the Americas as a turning point for civilization.

Williams set the stage for the other speakers by talking with the white audience members about the impact of emancipation: “How few of the happy, prosperous, and eager living Americans can appreciate what it all means to be suddenly changed from irresponsible bondage to the responsibility of freedom and citizenship!” Williams argued that change had occurred swiftly following emancipation and many white Americans were ignorant of emancipation and its after-effects.

In response to Williams’ speech, Cooper similarly emphasized emancipation as a starting point. However, Cooper highlighted the uncertain situation that faced Black women following emancipation: “Since emancipation the movement has been at times confused and stormy, so that we could not always tell whether we were going forward or groping in a circle.” Cooper also emphasized the importance of education to Black Americans’ futures.

VanderHaagen argues that Coppin’s speech positioned emancipation as a turning point and challenged white women on the progress that they had made by comparing it with the progress Black women had made: “For if we [Black women] have been able to accomplish anything … in what are considered the higher studies, or if we have been able to achieve anything by heroic living and thinking, all the more can you [white women] achieve it.”

While Coppin compared Black women favorably with white women, Early used statistics to describe how Black women had organized themselves between 1865 and 1893 and argued that “the organized efforts of … [Black] women have contributed to the elevation of the race and their marvelous advancement in so short a time.” Looking at the progress made in only 28 years, Early foretold even more progress to be made in the coming years.

Similarly, VanderHaagen argues that Brown “insist[ed] even more forcefully that Black women be judged only according to their own timeline.” Indeed, Brown highlighted the progress made since emancipation by saying, “Twenty-five years of progress find the Afro-American woman advanced beyond the most sanguine expectation.” Brown also focused on the future and spoke of hope for “centuries” of progress.

Harper mentioned emancipation only once, instead largely focusing on women’s empowerment. VanderHaagen argues that it was a deliberate choice by Harper to focus on all women. According to VanderHaagen, the sole reference to emancipation “could have been interpreted generally to apply to all women or specifically by Black women listeners to mean the end of enslavement. Either way, emancipation is represented as a time marking the promise of future progress.”

Remembering Enslavement

In the late 19th century, white Americans had recast slavery as “an inoffensive institution.” These speakers countered that narrative. According to VanderHaagen, Williams’s speech directly responded to white Americans’ perceptions of Black Americans’ moral failings by blaming enslavement, saying, it was “unavoidable to charge to that system every moral imperfection that mars the character of the colored American.” Cooper, who was personally familiar with the struggles of enslaved women, spoke of the destitution that faced freed people who had “no homes nor the knowledge of how to make them, no money nor the habit of acquiring it, no education, no political status, no influence.” VanderHaagen argues that Cooper’s speech focused on Black women as survivors.

Early spoke of enslavement using light and dark metaphors, describing it as “the long night of oppression, which shrouded their minds in darkness, crushed the energies of their soul, robbed them of every inheritance save their trust in God.” Brown called out white Americans for their roles in dehumanizing and brutalizing Black women. VanderHaagen argues that Brown “also directly correlated the enslaved woman’s deprivation and the white man’s enrichment.”

Black Women’s Agency

Within Black feminist thought, agency, which is defined by Black women’s self-determination and ability to act on their own behalf, is particularly important. VanderHaagen argues that the women enacted Black feminist ideals by asserting their agency as individuals by speaking at the WCRW. The women drew attention to Black women’s experiences of race and racism and to the possibilities for future change, which aligns with the emphases of Black feminist thought in the 21st century.

Williams described how a Chicago bank chose not to hire a young Black woman because of her race. Cooper told the audience about how enslaved Black women and mothers attempted to protect children from abuse. Brown, wearing an outfit created by students at Tuskegee, spoke of the students’ technical expertise and how they had learned the skills quickly as “girls who six months ago could handle only the hoe and the plow.”

VanderHaagen argues that “these speeches also demonstrate the significance of self-definition or self-determination.” Early focused on how Black women created organizations in their communities after emancipation and argued that “our people have shown a self-dependence scarcely equaled by any other people” (emphasis original). Early offered statistical evidence to show that Black women had created thousands of women’s associations.

Conclusion

VanderHaagen argues these speeches drew attention to the ways that Black women had been left out of the narrative of “progress” presented at the WCRW. According to VanderHaagen, “These speakers furthermore argued that only Black women could meaningfully characterize their own progress.” They did so by focusing on the importance of emancipation, speaking about the evils of slavery, and asserting Black women’s self-determination—a key emphasis of contemporary Black feminist thought.