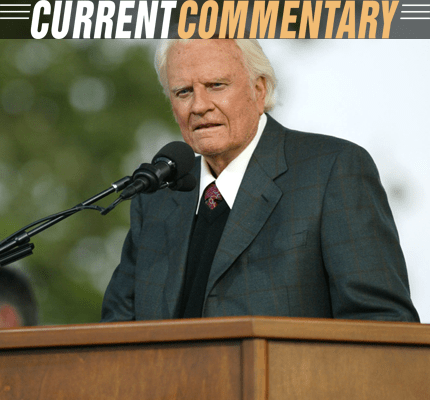

Billy Graham and the Power of Media Celebrity

By Mark Ward Sr.

Encomiums of the late Billy Graham, who passed away February 21, 2018, at the age of 99, applaud his career as a worldwide crusade evangelist, spiritual advisor to U.S. presidents, and elder statesman of American Protestantism.[i] Yet the tale of “America’s Pastor” illustrates how mass media and celebrity culture became, over the course of the 20th century, the arbiters of American popular culture—and of popular religion.[ii]

Graham was a uniquely American media creation. His career affirms the continuing relevance of “para-social relationships,” in which, according to the classic media theory, fans develop feelings of intimacy for favorite stars by watching them repeatedly on television or film.[iii]

Yet Graham’s career also corroborates more recent theories that focus on ties among audience members rather than with stars. In this view, media celebrities function as channels through whom fans monitor what other audience members with the same interests are watching, experience shared ritual occasions as each program airs, and become an integrated community.[iv] The proposition that American evangelicals became such a community through the power of media and celebrity finds no greater example than Billy Graham.

The Uses of Celebrity

Before Graham was a media darling, he was drawn into the evangelical community through the power of celebrities who preceded him. The first evangelical media celebrity was Dwight L. Moody, who in the 1870s gained worldwide fame by leveraging technological breakthroughs in cheap, mass-circulation printing. The evangelist realized that publicity in the “penny press” swelled audiences for his major-city crusades, while editors discovered that puffing his civic spectacles boosted circulation.

A generation later, in 1934, Graham was drawn to such a spectacle when the teenager was converted by a nationally prominent evangelist who crusaded that summer in Graham’s native Charlotte, North Carolina. Soon, Graham enrolled in Bob Jones College on the reputation of its celebrity evangelist-founder. During his college years, through his 1943 graduation from Wheaton College, Graham was integrated into the celebrity culture of mid-century American evangelicalism as he met “legendary preachers whom I had only heard about.”[v]

Finding that celebrity was the coin of the evangelical realm, Graham quickly learned its uses. After Wheaton, he took a Baptist pastorate in a nearby Chicago suburb. A few months later, with help from a prominent Chicago radio preacher, he used the church as a base to broadcast his own local Sunday night radio program. To pack his pews, he talked a renowned gospel recording artist into moonlighting on his broadcasts. Graham himself cued his on-air sermons to news events reported that week on the radio and cultivated a clipped and rapid-fire speaking style patterned after the popular radio commentators of the day.

But Graham had national ambitions. During the war years, an evangelical youth culture had emerged through the popularity of two national network radio broadcasts, Young People’s Church of the Air and Word of Life Hour. When a “Youth for Christ” organization was founded in Chicago by another radio preacher, Graham in 1945 quit the pastorate and signed on as staff evangelist. That first year, he logged 135,000 air miles, was named United Airlines’ passenger of the year, and drew his first press attention as the “Bobby Soxer Evangelist.”

Soon after becoming a full-time independent evangelist, Graham scheduled an ambitious Los Angeles Crusade for a three-week run in September and October 1949.[vi] Results were mixed, and the crusade was preparing to shut down, when something new to American culture happened—a celebrity conversion.

First was a cowboy movie actor, then a notorious West Coast mobster. Newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst ordered his editors to “Puff Graham.” Suddenly, national reporters thronged the “Canvas Cathedral” tent in Los Angeles. More celebrity conversions followed, including that of Olympic athlete and war hero Louis Zamperini, whose experiences as a Japanese prisoner of war are told in the recent book and film, Unbroken.[vii]

A year later, the unexpected death of Walter Maier, then the nation’s preeminent radio evangelist, inspired Graham to fill the void. With $25,000 collected in a shoebox after a crusade in Portland, Oregon, he launched the Hour of Decision in November 1950 over the newly formed ABC radio network.[viii] Graham also filmed his crusades and aired them as occasional television specials. In 1957, live ABC telecasts of his New York Crusade generated more than 1.5 million letters, including 330,000 “decisions for Christ.” With the triumph of this civic and media spectacle, his career was set.[ix]

The Power of Celebrity

Sixty years ago, conservative Christians were split between “fundamentalists,” who preached cultural separatism, and “evangelicals,” who favored cultural engagement. Graham controversially spurned fundamentalist sponsorship of his New York Crusade and cooperated with mainline Protestant churches.

By then, however, Graham was such a media celebrity that he carried “evangelicals” into the ascendancy, forever changing a movement with which one in four Americans now identifies.[x] Without this watershed, today’s evangelical engagement in American politics and culture war cannot be understood.

At the same time, Graham fits into a continuous stream of evangelical media celebrities: Dwight Moody, Billy Sunday, Graham himself, Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, Joel Osteen, and many others. Evangelicals have endured as a cohesive community across time and space, even across traditional denominational lines, for some 150 years.[xi] In large measure, this is because the community’s shared aspirations and fears are historically channeled through a succession of media celebrities whose words and images are disseminated via print, radio, television and now, on a vast scale, digital media.[xii]

In this way, evangelicals are a type of “interpretive community.” Such a community is formed by media users who view, hear, or read the same media genre—whether Star Trek or televangelism—and who bond over a shared interpretation.[xiii] Thus, “Trekkers” bond over futurism, and evangelicals bond over culture war.

Today, the vast proliferation of media choices lets people pick and choose the celebrities and communities that appeal to them most. Yet this same phenomenon increasingly fragments American society into media enclaves that have less and less in common. In such a media environment, it seems unlikely that anyone will ever succeed Billy Graham as “America’s Pastor.”

References

- [i] Laurie Goodstein, “Billy Graham, 99, Dies: Pastor Filled Stadiums and Counseled Presidents,” February 21, 2018, New York Times.

- [ii]Laurie Goodstein, Flora Lichtman, and Carrie Halperin, “Billy Graham: Media Pioneer,” February 21, 2018, New York Times [video].

- [iii] Donald Horton and R. Richard Wohl, “Mass Communication and Para-social Interaction: Observations on Intimacy at a Distance,” Psychiatry 19 (1956): 215-229.

- [iv] David Holmes, Communication Theory: Media, Technology, and Society (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005).

- [v] Billy Graham, Just As I Am: The Autobiography of Billy Graham (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1997), 44.

- [vi] “Into the Big Tent: Billy Graham & the 1949 Christ for Greater Los Angeles Campaign,” Billy Graham Center Archives.

- [vii] “After Unbroken: The Rest of the Louis Zamperini Story,” Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

- [viii] “November 5, 1950: First episode of the Hour of Decision radio program,” Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College.

- [ix] “1957—New York City—Billy Graham: A Crusade Remembered,” Billy Graham Center Archives.

- [x] “America’s Changing Religious Landscape,” Pew Research Forum, May 12, 2015.

- [xi] Mark Ward Sr., “Give the Winds a Mighty Voice: Evangelical Culture as Radio Ecology,” Journal of Radio and Audio Media 21 (2014): 115-133.

- [xii] Mark Ward Sr., “Digital Religion and Media Economics: Concentration and Convergence in the Electronic Church,” Journal of Religion, Media, and Digital Culture 7 (2018): 1-32.

- [xiii] Thomas R. Lindlof, “Media Audiences as Interpretive Communities,” Communication Yearbook 11 (1988): 81-107.