The “Optics” of Political Communication

In late February of 2012, just days before the critical Michigan Republican primary, leading candidate Mitt Romney set out to give a headline-grabbing policy speech that would explain his plan to revive the struggling economy. But after security concerns prompted the speech to be moved to the cavernous Ford Field football stadium, the news media fixated on the near-empty stadium instead of the content of Romney’s speech. Although 1,200 supporters were there, the 65,000-seat stadium looked empty. The poor visuals – what political insiders would call bad “optics” – overpowered Romney’s desired message and the Romney campaign confirmed an important political principle: it is not just what politician say or write that matters, equally important is how politicians look and visually present themselves. For political communication audiences, what they see as just as important as what they hear or read.

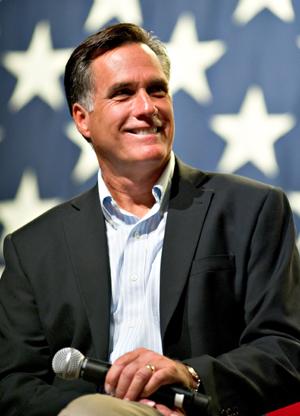

Most American’s do not experience political leaders first hand; they instead rely on the media to learn about their elected officials and candidates for public office. One of the primary means citizens learn about those leaders is through pictures. Experimental research in political communication has found that a single photograph of a candidate can influence voters’ judgments regarding that candidate’s demeanor, competence, leadership ability, attractiveness, likeableness, and integrity.

Like a homebuyer looking for a new house, voters base a great deal of their political opinions on the first impression of a politician – a candidate’s “curb appeal.” This “curb appeal” is the emotional response voters get when they first see a candidate on television. These “curb appeal” pictures provide viewers with mental shortcuts about the candidate’s background, personality and demeanor, and directly shape a candidate’s image. Politicians, for example, may build a “compassion” image by appearing with children, family members, admiring supporters, or religious symbols or they may communicate “ordinariness” by appearing in casual or athletic clothing, linking themselves to common folk by visiting disadvantaged communities, or depicting themselves participating in physical activity such as chopping wood, clearing brush, or hunting. In short, visual images can shape and construct political images.

Politicians understand the significance of visuals and work equally hard to construct effective image bites as they do powerful sound bites. “Optics” are a daily concern in politics and politicians will go to great lengths to insure their message is effectively communicated visually. For example, to demonstrate their unity after the long and contentious 2008 primary, Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton held a joint rally in Unity, New Hampshire in which the candidates hugged and smiled in color-matched outfits, delivered nearly identical speeches, and stood in front of huge letters spelling U-N-I-T-Y.

There are countless other examples of this visual image making: George W. Bush’s tailhook landing aboard a homecoming aircraft carrier, Ronald Reagan associating his presidency with the American west and the mythic cowboy, and Bill Clinton playing the saxophone. A negative visual, of course, can also create and reinforce negative perceptions, such as when Lyndon Johnson was photographed lifting his beagle by the ears, when Michael Dukakis put on a giant helmet and goofy grin in an M1 Abrams tank in 1988, or when Bob Dole was filmed falling off a stage during a campaign event in 1996.

Just as politicians have speechwriters to craft memorable speeches, they also have “advance staff” and event planners to create emotional and resonant images. Image-makers attempt to control the politician’s dress and facial expression, lighting, setting, backdrop, and other elements in the visual frame. Media events are staged such that photographers and videographers are limited to favorable camera angles selected by the campaign.

It is political folklore that Americans who watched the first 1960 presidential debate on television preferred the photogenic Kennedy, while those in the hall and listening via radio favored less visually appealing Nixon. A now a growing body of research finds that there is truth to this story. Overall, research has shown that visual images are often more persuasive than written or spoken communication because they communicate easy-to-understand information more quickly and memorably. Specifically, empirical studies have found: (1) people believe what they see more than what they read or hear, (2) when visual and verbal messages are in conflict, viewers have difficulty remembering the verbal information, and (3) visual messages override other messages when processed simultaneously.

One of the most important visual symbols in politics is a candidate’s facial expression and physical appearance. In as little as a tenth of a second, voters form opinions of the candidates based on a candidate’s facial expression. Studies have also shown that attractive candidates not only get more votes than unattractive candidates; attractive candidates are also seen as more competent, trustworthy, and qualified. A great deal of voting appears to be driven, at least in part, by the physical appearance of politicians.

Another common visual symbol in politics is the American flag. Candidates frequently surround themselves with American flags to take advantage of the flag’s patriotic, historical, and mythic symbolism. American flags are ever present and ubiquitous at campaign events and in political advertisements. Candidates will go to great lengths to be photographed with the American flag—for example, George H. W. Bush once held a media event at a flag factory.

Images of political leaders with troops or military equipment are also widespread, especially during wartime. Politicians will commonly visit injured troops, don military uniforms, and tour weapons production facilities. These images tap into the “rally around the flag” emotions citizens typically have for soldiers and associate the political leader with strength and commitment to national defense.

Crowds are yet another frequently used visual. Boisterous crowds show that the candidate is popular, widely supported, and has momentum in the campaign. Pictures of the candidate juxtaposed with cheering supporters, packed speech halls, and autograph seekers also make a “social proof” argument in which politicians who are popular must be good. Celebrities, such as movie stars, well-known athletes, and musicians, may also appear with the politicians to indicate mass appeal or credibility.

Dan Bartlett, President George W. Bush’s communications director, said, “[political communications staff] pay particular attention to not only what the president says but what the American people see.” Bartlett is right. What a politician says is very important, but the message that is communicated visually and nonverbally is equally significant. In some cases, such as Romney’s speech at Ford Field, the “optics” of an event become the story. As the Internet increases as a source for political information and as more Americans get their news from short web videos or 140-character tweets, the importance of visual communication in politics will likely increase.

As voters follow the 2012 campaign, they will undoubtedly be faced with a vast collage of political images, each visual vying for attention and attempting to persuade. There are a few basic questions voters can ask when confronted with an image. First, identify the claim or argument that the visual is making. Is the argument fair and sound? Is the image authentic or is it manufactured? What type of evidence or reasoning is provided to support the visual argument? Second, who created the image and why? What was the motive of the image maker? Try to discern the point of view of the person that created the image. Last, does the visual attempt to manipulate the viewer or overwhelm the viewer’s thought process with emotion or fear? Does the visual attempt other voices from being heard or attack groups or individuals?