“Selling Singapore to Singaporeans:” Neoliberal Rhetoric in Singapore

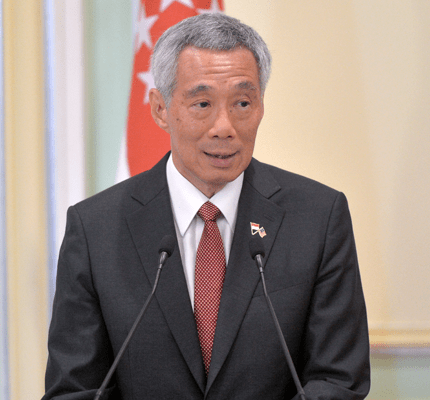

Governments around the world often turn to the language of business to promote themselves to voters, arguing that business principles undergird sound political leadership. For example, public figures, such as Donald Trump in the United States and Narendra Modi in India, have recently run for and been elected to political office on platforms emphasizing their business acumen. The language of business has long been a mainstay in Singaporean politics, and is a defining feature of Singapore's incumbent government, led by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong (LHL).

In a new article published in the NCA journal Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, College of Wooster Assistant Professor of Communication Rohini S. Singh conducts a rhetorical analysis of Singapore's 1960 to 2018 National Day Rally addresses, akin to State of the Union addresses in the United States. Singh argues that the Singapore government constructs an image of the nation as a corporation with a product to sell and a brand to protect.

Singh writes that by constructing the nation as being bound by economic concerns rather than sociopolitical ones, Singapore is engaging in neoliberal rhetoric.

Singh writes that by constructing the nation as being bound by economic concerns rather than sociopolitical ones, Singapore is engaging in neoliberal rhetoric. Neoliberalism is a philosophy that attempts to apply the logic of the market to other institutions, such as the government. In other words, under neoliberalism, governments are seen as offering a product or service to their citizens, and citizens are treated as “shareholders” in a corporate nation.

Singh’s analysis focuses on the People’s Action Party (PAP), which has been the dominant political party in Singapore since 1959. While studies of neoliberalism often focus on Western nations, Singh argues that Singapore represents “the end of the line” in neoliberal thinking because, for example, Singapore’s government “actually do[es] dispense dividends and bonuses to citizen-shareholders in years of good economic growth.” In addition to distributing these dividends, Singapore’s government employs private sector practices, including requiring that presidential candidates have prior chief executive officer experience and offering “million-dollar salaries” to cabinet members.

Singh identifies two ways in which Singapore’s presidents have incorporated neoliberal rhetoric into National Day Rally addresses: “locating national character in the performance of the economy” and “packaging and selling the nation to the people.”

Singapore’s leaders have emphasized that Singapore’s “national character” is connected to its economic performance. Although Singapore is a geographically small nation, its leaders emphasize that its economic performance allows it to “punch above its weight.” Indeed, in 2009, LHL said, “Singapore is not just the name of a country, but also an icon of quality,” and later referred to “the Singapore brand.” Singh argues that Singapore’s leaders sell this brand to Singapore’s citizens by packaging the nation as a product to be consumed by the citizen-customer.

According to Singh, Singapore’s leaders “sell Singapore to Singaporeans” in several ways. First, the government presents policies as a “pre-determined product” by emphasizing the government's exclusive expertise in designing policies. By brandishing its ostensibly exclusive policy design expertise, the government suggests that there is little cause – or space – for citizens to question policies. Instead, the citizen's role is to consume policies which are, Singh argues, often wrapped in “alliterative brand-speak.” A typical example of such “brand-speak” is when the prime minister called in 2011 for a public consultation exercise to "reaffirm, recalibrate, and refresh” the relationship between the people and the government.

Singh contends that alliteration, or the repetition of sounds and words, such as in “Kit Kat” and “Best Buy,” is more than a marketing ploy to make brands memorable. Instead, its tight pattern exercises a kind of rhetorical authoritarianism which “suggests that alternative iterations are not possible because they would break the coherent formation of neat parallel sounds and matching letters.” Although the use of alliteration is not unique to Singapore, Singh argues that its pervasive use by the PAP “gives the impression of leaders who have already worked out all the answers. After all, why would anyone need to question a policy created by a government with such a complete view of every situation that they are able to conceptualize it from on high from start to end, and then categorize it into tripartite labels with neat matching letters—the rhetorical equivalent of tying up a parcel with a bow?”

A second strategy by which the government packages its policies is to present the National Day Rally as a “product launch.” Much like an Apple product launch, the National Day Rally emphasizes what’s new and available to be consumed. The prime minister uses a clicker to navigate a large slideshow of demographic data, financial information, promotional photographs, and video testimonies about new government projects. Singh notes that on one occasion, LHL even acted as a real estate agent while talking through a new public housing option, enthusing about its “million-dollar views.” Finally, according to Singh, the “growth dividends” the government distributes to citizens in years of economic plenty “invariably come across as giveaways to eager audiences.”

Singh concludes that the National Day Rallies frame the relationship between citizens and the country as a primarily economic relationship. Consequently, when there is no economic reason to stay, or when economics dictate that a job outside of Singapore would be better, citizens often leave.

Singh argues that this study contributes to a broader understanding of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism has frequently been described as an extension of liberalism in the West. For example, traditional liberalism advanced the idea of a free market; neoliberalism applies the ideas of the free market to other areas of life, such as by presenting government services as products. In the West, these arguments have often been accompanied by a belief in the ability of free markets to create the freest possible situation for all citizens, another core tenet of liberalism. Singh argues that Singapore demonstrates that neoliberal rhetoric is not always grounded in a “commitment to liberalism” because the “highly interventionist and authoritarian government [of Singapore] espouses no such commitment to liberalism.” Singh concludes that there should be further studies of neoliberal rhetoric outside of the United States.

Singh received the 2019 Outstanding Article Award from NCA’s Asian Pacific American Caucus & Studies Division (APAC/SD) for this article.