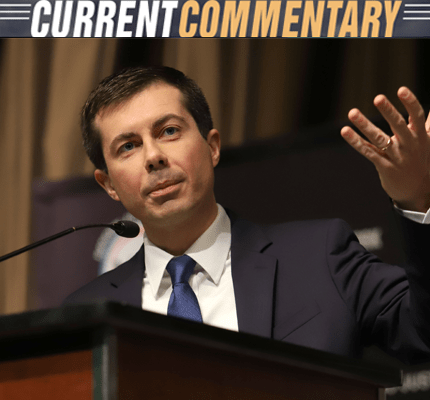

Pete Buttigieg’s Ethical Rhetoric of Civil Religion

By Peter Loge, M.A., M.S.

Former Presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg roots much of his rhetoric in appeals to a prophetic vision of American civil religion. Such appeals are effective, ethical, and can be used by candidates across the political spectrum.

When he announced his run for the White House in April 2019, Pete Buttigieg said, “I believe in American greatness. I believe in American values. And I believe that we can guide this country and one another to a better place.” (Buttigieg, 2019) When he dropped out of the race 13 months later, he told supporters that “…politics matters because leaders can call out either what is best in us or what is worst in us, can draw us either to our better or to our worst selves. Politics at its worst is ugly, but at its best politics can lift us up. It is not just policy making, it is moral.” (Buttigieg, 2020)

Buttigieg has since launched the Win the Era PAC and Action Fund, which says it will “work to embody and lift up the values that bring the American people together” and will support candidates who follow the Buttigieg campaign’s “Rules of the Road” – including a commitment to respect, truth, and responsibility. (Win the Era)

Buttigieg’s rhetoric appeals to a prophetic vision of American civil religion. Popularized by Robert Bellah in 1967, civil religion is a coherent putting together of who we are, where we came from, and how we should behave next. John D. Carlson described civil religion as a “collective effort to understand the American experience of self-government in light of higher truths and through reference to a shared heritage of beliefs, stories, ideas, symbols, and events.” For Philip Gorski and others, civil religion can be humble (prophetic) or imperialistic. A prophetic civil religion, to paraphrase Abraham Lincoln, worries less about God being on America’s side than it does about America being on the side of God.

This prophetic vision acknowledges that America is far from perfect. The man who wrote the phrase “all men are created equal” owned slaves, and we are reminded daily that racism continues to brutally stain America. A lot of people have been treated very badly in this country because of their language, faith, skin color, sexual identity, and more. Much of our history is ugly.

A prophetic civil religion sees redemption as possible. To borrow from Langston Hughes, it recognizes an America that never was, but that will be. (Hughes 1936) In American Covenant: A history of civil religion from the puritans to the present, Gorski borrows from Hughes to argue for a civil religion that strives for a “free people governing themselves for the common good.” Such a “righteous republic” is one that “demands that the political community protect the weak and downtrodden from the high and mighty” and also has an “egalitarian ethic.” (Gorski 2017, 224) These values, this political myth, is at the core of much of Buttigieg’s political rhetoric.

A nation is, in many ways, a rhetorical construction. As Michael McGee writes:

“One begins with the understanding that political myths are purely rhetorical phenomena…Such myths are endemic in the human condition and, though technically they represent nothing but a “false consciousness,” they nonetheless function as a means of providing social unity and collective identity. Indeed, “the people” are the social and political myths they accept.” (McGee, 1975, 247)

Borders matter; health care and taxes are different when one crosses from the United States into Canada. But the myth is critical. Because a nation is a story of itself, a “political myth,” facts matter less than a greater truth. As Richard Rorty writes, “Stories about what a nation has been and should try to be are not attempts at accurate representation, but rather attempts to forge a moral identity.” (1998, 13) On the stump and in his PAC, Buttigieg argues for a shared moral identity that is rooted in this prophetic vision of American civil religion.

In addition to being effective, this appeal to civil religion also is fundamentally ethical. Rhetorical scholar and conservative public intellectual Richard Weaver wrote that “rhetoric at its truest seeks to perfect men by showing them better versions of themselves, links in that chain extending up toward the ideal, which only the intellect can apprehend and only the soul have affection for.” (1953, 25) This is precisely what Buttigieg’s political rhetoric attempts. Unlike other politicians who argue from ethically suspect and less effective appeals to cause and effect, circumstance, authority, or similarity (Weaver 1963, 1049-50), Buttigieg argues from a transcendent truth to speak to the needs of the moment – he speaks to “historical man.” (Weaver 1963, 1046)

A lot of voters supported Buttigieg’s vision for how politics should be conducted. Joe Biden’s presidential campaign has adopted the Rules of the Road, and the Win the Era PAC is raising money and helping candidates.

Support for Buttigieg’s rhetorical approach is not the same as support for his policies. Appeals to civil religion have a long, bipartisan history (i.e., Adams 1987, Hankins 2004). Peter Wehner has applauded Buttigieg’s political approach, while making it clear he disagrees with Buttigieg on important issues. (Wehner 2020) And, fellow conservative commentator Jennifer Rubin has similarly sung Buttigieg’s praises, while disagreeing with all of his ideas. (Rubin 2020)

Candidates with a wide range of ideas can work from the same, ethical, rhetorical premise as Buttigieg’s: a rhetoric that imagines a better America that humbly approaches its own history while working toward a more perfect union.

Media Resources

Robert E. Denton, Jr., Virginia Tech, rdenton@vt.edu

David A. Frank, University of Oregon, dfrank@uoregon.edu

Trischa Goodnow, Oregon State University, tgoodnow@oregonstate.edu