How New Orleans Activists Held a “Second Line to Bury White Supremacy”

There are more than 700 Confederate monuments on public property in the United States. These monuments promote Lost Cause memories of the Civil War that sympathize with the Confederacy. While some civic leaders and groups argue that the monuments merely represent history, others argue that they symbolize racial oppression and white supremacy. ake ’Em Down NOLA, an activist collective based in New Orleans, notes on its website, “These memorials only serve as constant reminders of the past and present domination of black people by the rich white ruling class.”

In 2015, the New Orleans City Council voted to remove four Lost Cause monuments that were positioned in high-traffic areas where tourists and locals regularly saw them. Ultimately, these monuments would be removed in 2017. In a new article published in NCA’s Quarterly Journal of Speech, J. David Maxson theorizes that the removal of the monuments created an opportunity for New Orleanians to address lingering residual memories. Maxson argues that the absence of the Liberty Place Monument left a residual memory and created the opportunity for the community to reimagine how the space that once contained the monument relates to the past, present, and future of the community.

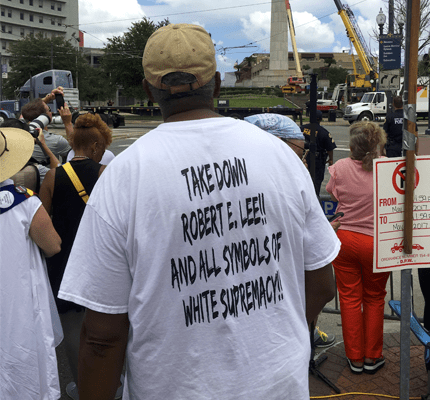

Maxson used rhetorical field methods to analyze Take ’Em Down NOLA’s Second Line to Bury White Supremacy. A second line is a celebratory brass band parade developed and sustained by New Orleans’ black neighborhood communities where participants—known as second liners—follow the band and dance. The author observed and participated in the second line; Maxson collected extensive field notes, photos, and audio recordings. Through the second line, the participants used an iconic New Orleans cultural practice to celebrate the removal of the Lost Cause monuments.

The author’s analysis of the second line focuses on the Liberty Place Monument, which memorialized what Maxson describes as a “highly orchestrated skirmish” in September 1874, in which members of a white supremacist group fought city and state police officials to assert white people’s right to control local politics. Thus, Maxson argues, “At no point in its history was the obelisk a neutral artifact that impartially recounted the details of an historic event. Instead, from the moment of its dedication, the Liberty Place Monument functioned as an explicit symbol of white supremacy that white politicians frequently referenced to justify Jim Crow policies.”

On April 24, 2017, the Liberty Place Monument was dismantled in the pre-dawn morning hours. On May 7, 2017, before three other Confederate monuments were removed, Take ‘Em Down NOLA organized a second line to commemorate the removal of all four Lost Cause monuments. This public commemoration occurred as a result of City Hall’s initial refusal to officially celebrate the removals.

Maxson argues that Take ’Em Down NOLA’s second line was conducted within a larger history of mock jazz funerals and public parades. Black residents of New Orleans often used such gatherings to resist white supremacy, such as the February 1865 “two-day funeral service celebrating ‘the Death of American Slavery.’”

At Take ’Em Down NOLA’s second line, Maxson saw second liners and speakers directly address how the second line challenged white supremacy. A poet and co-founder of Take ’Em Down NOLA named “A Scribe Called Quess?” told the crowd, “I love my city; we all love our city. If we could only aim our music in the right direction—not just to the hearts, but to the minds. This is the most African city you gonna find in North America. We’re just dominated by symbols of white supremacy; that’s a crime. Somebody say, ‘That ain’t right.’ (Second liners: That ain’t right!) Ain’t right at all.”

In addition to the statements made by participants, the route of the second line was also structured to acknowledge the violent history of Confederate monuments in the city. The second line began at Congo Square, birthplace of jazz, and ended at the Robert E. Lee statue. Along the route, the second line stopped at the intersection where the Liberty Place Monument once resided. When the second line arrived at that intersection, Angela Kinlaw, co-founder of Take ’Em Down NOLA, told the crowd, “As we move forward, to the left, be reminded that’s the former location of the white supremacist monument” (emphasis original).

Some second liners also carried enlarged photos of Reverend Avery C. Alexander, who led a protest during the rededication of the Liberty Place Monument in 1993. The Liberty Place Monument was previously removed in 1989. However, after a court battle, it was reinstalled in a less prominent location in 1993. At one point during the 1993 protest, a police officer put Alexander in a chokehold. The photo appeared in the New Orleans Times-Picayune the following day and led to widespread outrage. By carrying this iconic photo during the second line, Maxson argues that Take ’Em Down NOLA second liners drew a visual connection between the Liberty Place Monument and violence against people of color.

Maxson notes that Take ’Em Down NOLA’s second line served as an example of how one grassroots group shifted the residual memories of the Liberty Place Monument. Instead of focusing on Lost Cause myths of the Confederacy, the second line focused both on the role of the monument in the oppression of the city’s people of color and on how local activists used the space around the monument to resist white supremacy.