Between Geopolitics and Oligarchy

TikTok is indeed everywhere— on our phones, in the news, even in our classrooms. Just the other day in my class on global digital cultures, an undergraduate student presented a case for TikTok as a “cultural infrastructure,” a day-to-day, routine app for the younger demographics that surround our scholarly endeavors. Beyond that, TikTok turns up in class discussions whether students are talking about global events, trends in popular culture, or issues of gender performativity. It seems like there’s a niche for everyone on TikTok. Perhaps it’s the algorithm that binds us. At a time when the neoliberal machine has isolated as atomized individuals, we will probably take that niche as long as we can find others like us—for good or for bad. As is the case globally, within the U.S., too, TikTok has achieved some measure of “cult” status among its users, with thousands flocking to the platform for their daily dose of entertainment, commerce, and even news. TikTok does seem to have taken over the public imagination in a very significant way, at least for some demographics in the country.

But as much as it has been embraced, TikTok has also been at the center of controversy, the subject of vitriol, and the target of bans. Several countries around the world have considered and enforced total or partial bans of the platform.1 One could argue that perhaps the stage has been set by China itself where TikTok’s Chinese version Douyin is available, but the TikTok that that users in other parts of the world know, remains largely inaccessible due to the country’s unique internet governance situation.2 But to pin this on China’s censorship alone would be an oversimplified explanation of a complex problem. At the root of this problem lies the myth of boundless connectivity.

From time to time, the discourse of a free internet as the pathway to democracy keeps raising its head. In the 1990s, internet activist John Perry Barlow envisioned a free and radical cyberspace, unfettered by government control. But Barlow’s manifesto— “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace”— was a response to the Telecommunications Act of 1996 that turned the internet into a marketplace for large corporations, creating oligarchies instead of the deregulated space it promised.3 In a sense, the Declaration was a response to the very erosion of the “independent” horizons of cyberspace. While it seems disconnected from what is happening now, it is pertinent to return to this history precisely because later invocations of the internet’s radical power have often picked up on the rhetoric of Barlow’s declaration— the coming of a “civilization of the Mind in Cyberspace”— without addressing the material realities of its impossibility. Take Meta for instance; in its public messaging Meta claims to “give people a voice,” speaking in the language of the common good.4 But the stark realities of Facebook’s operation have pointed in a diametrically different direction, be it the Cambridge Analytica scandal,5 or its culpability in the propagation of hate against the Rohingya in Myanmar.6

Communication scholar Sangeet Kumar characterizes such public-facing messaging as a philanthropic trope peddled by tech-corporations, whereby their missionary avowal of spreading digital connectivity as a human right belies the financial motives underlying their ventures.7 Indeed, there is sufficient evidence from the recent past for us to not believe in such corporate messaging—platform capitalism is not here to free us. In the end, it is the realities of geopolitics and the machinations of tech-corporations that bear upon what apps (and their users) can or cannot do. TikTok is no different.

What is interesting about this TikTok moment though, is that the geopolitical trap speaks in one tongue while operating in another. Most countries that seek to restrict or ban the use of TikTok, the U.S. included, do it in the name of a security threat from China. In doing so, they perpetuate the same logic of censorship that they claim to be pushing against. China, in that sense, becomes a geopolitical shorthand— a brand that marks the skin of the platform— while the language of philanthropy allows Euro-American platforms to maintain legitimacy despite evidence that suggests otherwise. But behind this is the question of ownership. It is perhaps TikTok’s hold over the U.S. market that has come to be its undoing.

Writing in a September 2022 article for The Telegraph, Andrew Orlowski theorizes that what is going on is, in effect, “asset seizure.” According to him a combination of TikTok’s successful algorithm and the fact that it was “trouncing Silicon Valley at its own game” meant that with the coming of Trump 2.0 with a hardline stance against all things China, the time was ripe for a U.S takeover of the company.8 As I write this in October 2025, rumors of a tentative “TikTok deal” are already doing the rounds. December 16, 2025, is the deadline extension for ByteDance to comply, or face a ban under the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act.9 While there are reports that China has agreed to the deal, there is still speculation that the deal may collapse.10

David Frum reports in The Atlantic that behind the plan to have ByteDance sell its U.S assets or risk a ban lies a strategic scheme to keep the investors limited to hand-picked oligarchs without necessarily making any “substantive changes to the way that users’ data will be collected and stored”— a key security rationale behind the threat of banning the app.11 Of the many names that have been suggested as key players if the American ownership should come to pass are Larry Ellison, co-founder and CTO of Oracle Corporation, Michael Dell, CEO of Dell Technologies, and media-magnates Rupert Murdoch and Lachlan Murdoch— among other things, Chairman Emeritus and current CEO, respectively, of Fox Corporation.12 Also in the mix is the venture capital firm Andreessen-Horowitz, co-founded by Marc Andreessen.13 Andreessen is a bit of an internet legend as the co-author of the now-legendary Mosaic web browser, and co-founder of the Netscape Communications Corporation that was behind the equally important browser, Netscape Navigator. Lately, he has also been an adviser to the Trump administration,14 and a harsh critic of DEI initiatives in higher education.15 It is also rumored that Donald Trump’s youngest son, Barron Trump, is “in the running for a top job at TikTok.”16 All of this, of course, is yet to pass. Yet, there is enough to suggest that the 2025 TikTok moment is as much about corporate play and oligarchic consolidation— a nexus between platform capitalism and hyper-nationalism— as it is about containing Western liberal democracy’s “Other.”

This has happened before…it may happen again (and again)

An important lesson is to be learnt from the fact that while this is an emergent situation in the U.S., it has happened already elsewhere. Take India, for instance, whose digital ecology is the primary subject of my research. In 2020, India banned TikTok and a host of other Chinese apps after border disputes with China. At the time, India was TikTok’s largest market outside of China.17 In India, TikTok was a safe haven for many newly online users, especially those from marginalized social positions (lower class, oppressed caste, or rural) for whom the app was an opportunity to be seen and heard in ways that are usually not available to them. With an intuitive interface that supported India’s multi-lingual fabric, and with a library of songs that emerged from those regional linguistic formations, it is easy to see why the app became so popular throughout the country.18 However, India’s TikTok ban was sudden and overnight, leaving many creators and lay users locked out of the app for good.19

When the ban came into effect, a now-familiar political rhetoric surfaced. Led by the right-wing supremo, prime minister Narendra Modi, the Indian government declared that TikTok, along with a host of other Chinese apps had been banned because they were “prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of state and public order.”20 According to Emily Baker-White, author of a recent book on TikTok, that move did not go unnoticed; Trump had seen potential for a similar move and “ordered lawyers at the National Security Council to draft an executive order” similar to the Indian one.21 In some ways, the 2025 TikTok moment was five years in the making, and like all things global, it had happened elsewhere and it would travel transnationally—just not in the way we usually imagine global flows.

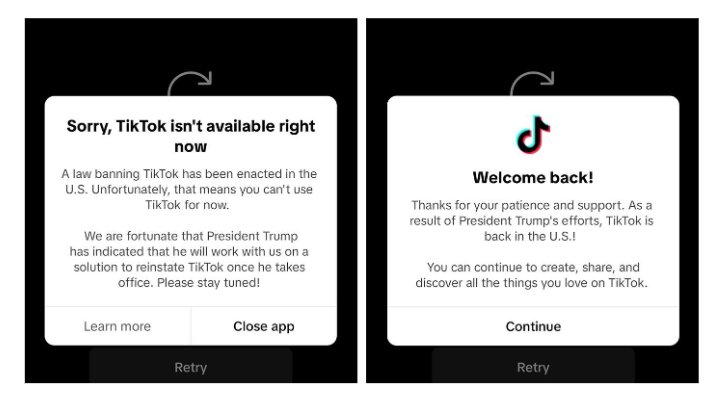

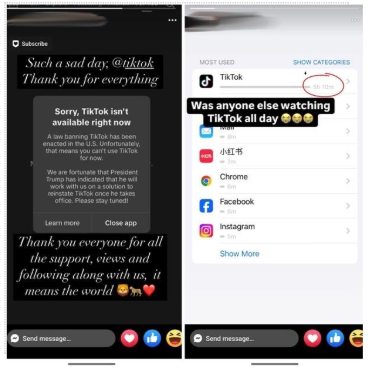

An important difference between the Indian and the U.S. situations is that in early 2025, the app came back online within a day in the U.S. In India five years later, the ban still persists. On January 18, 2025, TikTok suspended its services in the U.S., just hours before the ban went into effect.22 The app’s temporary suspension and return in January 2025 were all centered on the figure of Donald Trump. The day it went offline, U.S. users encountered a message about the legal reasons for its unavailability. It was followed by these words: “We are fortunate that President Trump has indicated that he will work with us on a solution to reinstate TikTok once he takes office. Please stay tuned!” When it came back on January 19, the app praised Trump for its efforts in bringing it back for U.S users. At Trump’s inauguration the day after, a host of tech and media figures were present—Elon Musk (Tesla/X), Jeff Bezos (Amazon), Tim Cook (Apple), Mark Zuckerberg (Meta), Rupert Murdoch (NewsCorp/Fox), Sundar Pichai (Google). Also in attendance: Shou Zi Chew, CEO of TikTok. Beyond the secret handshakes between these political and economic behemoths and what now seems like a prolonged game of bait and switch, lie thousands of users and creators whose love for the app, and in some cases, livelihoods are on the line.

So…what do we do now?

Nothing is certain yet, but there are two potential scenarios in this palpable multiverse of madness. First, TikTok could still be banned in toto and both creators and the researchers who study them will be scrambling for alternatives. Second, TikTok might not get banned, but under the new U.S. consortium control, the app could transform in nature— speculatively, this might mean either significant changes to its interface design, and/or given our political moment, it may entail changes in the way its algorithm operates, or limitations on what users can or cannot say and do on the platform. In either scenario, we would have to come up with strategies to cope with the mutating digital landscape. What does all of this mean for us as scholars of communication studies? How might we continue to conduct research about TikTok in this precarious scenario? While I have no definitive answers (this is an emergent situation, after all), my experience of writing about India’s TikTok moment while being located in the U.S has taught me some valuable lessons.

Researching Indian TikTok creators for my in-progress book manuscript has been a strange temporal and spatial experience. I was able to access TikTok’s Indian accounts in the past few years only when I was located in the U.S. At the same time, writing about them in the present felt almost like intruding into a frozen time-chamber. Like Miss Havisham’s mansion in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, time on Indian TikTok had stopped on June 29, 2020. When TikTok went dark in the U.S. in January 2025, farewell posts on social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook echoed similar reactions to the 2020 ban in India. As thousands of U.S. users poured out messages about losing access to their favorite app, I also feared losing access to whatever little of the snapshot of Indian TikTok that was left.

My takeaway from the experience— platforms come and go, and we have to adapt. There are multiple ways to continue research, no matter which direction the wind blows. For scholars of media industries and platforms, the ongoing saga about a potential ban or a deal is itself the subject of research. This is also true for those who are interested in questions of internet governance, as well as the tussle between surveillance and agency on platforms. For those interested in creators on these platforms the challenge may be greater. But platforms ecologies are not made only by the tech-corporations. Their design may originate in tech industry logics, but that provenance does not define their ultimate use. Platform ecologies are co-designed in practice by their users, and users will migrate.

In January, we saw this for a brief moment when public discourse centered on “TikTok Refugees” who moved to Xiaohongshu (RedNote), another Chinese platform. This was met with both a sense of possibility as well as a sense of wariness by those already on the platform who were now seeing swarms of new users populating the interface.23 It was an interesting moment— users were flocking to another app because of geopolitical forces, yet the move itself defied the security logic of the TikTok ban. At the same time, it highlighted a kind of flow that defies the “West, then the rest” imagination of globalization. That may soon happen again, depending on what December 2025 has to offer.

In India, the story was different as the ban was (and still is) total. The ban saw the rise of local platforms almost immediately after the ban, with apps like Moj, Josh and Chingari emulating the TikTok logic— something I discuss in a chapter of my book. But while they have seen some measure of success, they are nowhere near what TikTok was. On the other hand, Instagram introduced the “Reels” feature in August 2020. Although India was not the first country where the feature was launched (Germany, France and Brazil came first), its timing coincided with the direct aftermath of the TikTok ban in India.24 Reels have taken over from the TikTok craze in India, and while Instagram is not the great leveler that TikTok was socially, one could potentially track absences on the platform.

As scholars of media, communication and technology, our role is not only to examine what a platform enables and what is being said and done on platforms, but also who goes missing when ecologies transform and landscapes shift. In the Indian scenario, this has meant looking at other platforms, alongside tracking the disappearance or dispersal of some voices that TikTok amplified. In the U.S., this might be one possible line of emergence. We may also have to keep an eye out for what might happen if the deal comes into fruition and we are faced with a beast that has changed shape. In the end, TikTok too is a for-profit platform, so this is not an argument for the app as a by-design egalitarian enterprise by any means. But its users have found ways of forming niches that defy the “iron cage” of platform capitalism. What ultimately happens in the U.S. remains to be seen. What is undeniable is that we are in a moment of reckoning, and it is the subjects of this reckoning—the people who populate the app or disappear from the digital landscape, that our scholarship must be responsible to.

Notes

- Nita Bhalla, “US TikTok ban: Which other countries have banned the app?,” Context, February 14, 2025,

https://www.context.news/big-tech/us-tiktok-ban-which-other-countries-have-banned-the-app - Jessie Yeung and Selina Wang, “TikTok is owned by a Chinese company. So why doesn’t it exist there?,” CNN, March 24, 2023,

https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/24/tech/tiktok-douyin-bytedance-china-intl-hnk - John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, February 8, 1996,

https://www.eff.org/cyberspace-independence - “OUR MISSION: Build the future of human connection and the technology that makes it possible,” Meta,

https://www.meta.com/about/company-info/ - “‘The Great Hack’: Cambridge Analytica is just the tip of the iceberg,” Amnesty International, July 24, 2019,

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/07/the-great-hack-facebook-cambridge-analytica/ - Daniel Zaleznik, “Facebook and Genocide: How Facebook contributed to genocide in Myanmar and why it will not be held accountable,” The Systemic Justice Project, 2021,

https://systemicjustice.org/article/facebook-and-genocide-how-facebook-contributed-to-genocide-in-myanmar-and-why-it-will-not-be-held-accountable/ - Sangeet Kumar, The Digital Frontier: Infrastructures of Control on the Global Web (Indiana University Press: 2021): 50, 52

- Andrew Orlowski, “Trump’s TikTok deal sets a very dangerous precedent,” The Telegraph, September 22, 2025,

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2025/09/22/trumps-tiktok-deal-sets-a-very-dangerous-precedent/ - “H.R.7521 – Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act,” United States Congress,

https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/7521/text;

“FURTHER EXTENDING THE TIKTOK ENFORCEMENT DELAY,” The White House, September 16, 2025,

https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/09/further-extending-the-tiktok-enforcement-delay-9dde/ - Jessica Rawnsley, “US says ‘framework’ for TikTok ownership deal agreed with China,” BBC, September 15, 2025,

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5yj5xj78p5o;

Ralph Jennings, “With US-China tensions back on the upswing, is the TikTok deal at risk?,” South China Morning Post, October 15, 2026. - David Frum, “Trump’s Dodgy Plan for TikTok,” The Atlantic, October 11, 2025,

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2025/10/questions-trump-tiktok-deal/684519/ - Dan Whateley and Sydney Bradley, “Here’s what we know about who’s buying TikTok’s US business,” Business Insider, September 26, 2025,

https://www.businessinsider.com/who-could-take-over-tiktok-us-business-investors-oracle-ellison-2025-9 - “White House to hold meeting on TikTok,” Reuters, April 1, 2025,

https://www.reuters.com/technology/andreessen-horowitz-talks-help-buy-out-tiktoks-chinese-owners-ft-reports-2025-04-01/ - Eleanor Pringle, “Marc Andreessen says half of his time goes to helping Trump at Mar-a-Lago,” Fortune, December 11, 2024,

https://fortune.com/2024/12/11/marc-andreessen-half-time-florida-trump-business-policies/ - Nitasha Tiku, “Tech billionaire Trump adviser Marc Andreessen says universities will ‘pay the price’ for DEI,” The Washington Post, July 12, 2025,

https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/07/12/marc-andreessen-private-chat-universities-diversity/ - Owen Scott, “Barron Trump tipped for top job at TikTok after dad tells users they ‘owe’ him for saving platform,” The Independent, October 9, 2025,

http://the-independent.com/news/world/americas/us-politics/barron-trump-tiktok-job-trump-advent-b2842539.html - Krutika Pathi, “Here’s what happened when India banned TikTok,” PBS, April 24, 2024,

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/heres-what-happened-when-india-banned-tiktok - Yashraj Sharma, “Instagram has largely replaced TikTok in India, and erased working-class creators,” Rest of World, October 6, 2021,

https://restofworld.org/2021/instagram-and-class-in-india/;

Nitish Pahwa, “What Indians Lost When Their Government Banned TikTok,” Slate, August 7, 2020,

https://slate.com/technology/2020/08/tiktok-india-ban-china.html - Thomas Germain, “The ghosts of India’s TikTok: What happens when a social media app is banned,” BBC, December 6, 2024,

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240426-the-ghosts-of-indias-tiktok-social-media-ban - “Government Bans 59 mobile apps which are prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of state and public order,” Government of India Press Information Bureau, June 29, 2020,

https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=1635206 - Emily Baker-White, Every Screen on the Planet: The War Over Tiktok (New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc., 2025): Chapter 15, “American Puppet.” p. 125, Kindle Edition.

- Aaron Pellish and Brian Stelter, “TikTok shuts down in the United States hours ahead of a ban,” CNN, January 19, 2025,

https://edition.cnn.com/2025/01/18/business/trump-tiktok-ban/index.html - Yiyang Xiao and Jinjin Zhang, ““No longer our place”: TikTok refugees and the politics of digital migration to Xiaohongshu,” new media & society (2025): 1–20. DOI: 10.1177/14614448251368890; Amy Hawkins, “Chinese rival app Xiaohongshu is overwhelmed by ‘TikTok refugees’ in US,” The Guardian, January 18, 2025,

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/jan/18/chinese-rival-app-xiaohongshu-is-overwhelmed-by-tiktok-refugees-in-us - Katie Sehl, “Instagram releases Reels in India, following TikTok ban,” Hootsuite, March 11, 2021,

https://blog.hootsuite.com/social-media-updates/instagram/instagram-reels-in-india/

Anirban Baishya is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Communication Arts, University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research interests include new media and digital cultures, media aesthetics and politics, surveillance studies, and global media. His work has been published in journals such as International Journal of Communication, Communication, Culture & Critique, Text and Performance Quarterly, and Media, Culture & Society. His book project The Selfie Machine: Selfies, Platforms and Digital Image Culture in India (forthcoming from Rutgers University Press in 2026) examines the potentials and limits of self-imaging culture through selfies and short-videos as they intersect with market- and political- formations in contemporary India.