France en Marche: Communicating Hope

By Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager, Ph.D.

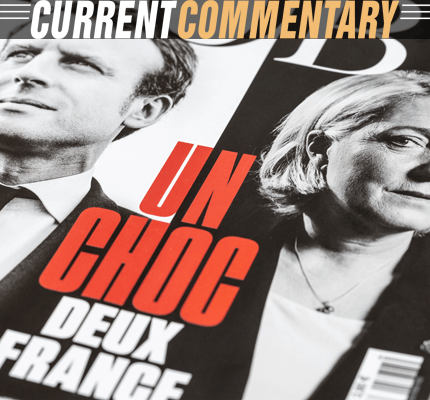

Around the world, observers held their breath as the French went to the polls. Would the Brexit and Trump momentum consume the French, or would liberal internationalism make a stand against xenophobia, nationalism, and isolationism? To the relief of many, Emmanuel Macron defeated the neo-Fascist Marine Le Pen in decisive fashion, winning roughly 65 percent of the popular vote.

Indeed, although primarily associated with Julius Caesar, veni, vidi, vici could quite accurately summarize Emmanuel Macron’s victory in the 2017 French presidential election. The youngest and the most pro-European candidate in the race, who had never run for elected office, Macron came, saw, and conquered the French public sphere and (literally and metaphorically) marched to the top. A founder of the En Marche! movement, Macron is a centrist who enjoys strong support from across the political spectrum. The Former Economy Minister, Macron intends to promote economic growth and opportunities, implement reforms, and modernize the French economy. Perhaps most importantly for those of us associated with NCA, Macron embodies communication practices that are rooted in sound evidence, fair arguments, ethical standards, and typically European norms of civility, if not elegance.

Initially, in the first round, 11 presidential candidates included Marine Le Pen, Emmanuel Macron, François Fillon, Benoît Hamon, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, Nathalie Arthaud, François Asselineau, Philippe Poutou, and Jacques Cheminade. The candidates represented a wide range of political standings—there were socialists and communists, democrats and republicans, extreme leftists and ultra-nationalists, and some strong centrists (Le Figaro, 2017, March 18). Although former President François Hollande of the Socialist Party was eligible to run for a second term, he declared in December that he would not seek reelection because of his low approval ratings. Interestingly, Hollande was the first French president since the end of World War II not to seek re-election. According to multiple polls, Socialist Benoît Hamon, Republican François Fillon centrist Emmanuel Macron, and ultra-nationalist Marine Le Pen were the strongest candidates. Despite François Fillon’s initially strong candidacy, revelations that he employed family members (including his wife) in possibly fictitious jobs negatively and significantly affected his popularity. Eventually, Fillon endorsed Macron. Mirroring the recent U.S. elections, at this point in France it seemed the preliminary election activities were based largely around eliminating candidates due to perceived flaws, not seeking the key themes or tackling the important questions that now haunt France.

The second round of the presidential election narrowed the candidates down to Emmanuel Macron versus Marine Le Pen: a pro-European centrist who aimed to modernize the French economy, condemn extreme forms of nationalism, protect the environment, and fortify transnational ties, versus an ultra-nationalist who aimed to exit the Eurozone (Frexit), re-introduce a French national currency, fortify French borders, and focus on national security by stopping immigration. Notably, Le Pen’s Front National gained popularity in light of multiple terrorist attacks in Paris in 2015 and 2016. This wave of terrorism triggered xenophobia and, more specifically, Islamophobia among many French voters. Nonetheless, as famously declared by legendary French president Charles de Gaulle, “patriotism is when love of your own people comes first; nationalism, when hate for people other than your own comes first.” May 7, 2017, demonstrated that an overwhelming majority of the French people still value patriotism over nationalism.

However, the French election also was impressively, almost alarmingly similar to the 2016 American presidential campaign – except, of course, in its drastically different outcomes. This is what the 2017 French presidential campaign looked and sounded like to millions of us, living in the America of President Trump, whose presidency in itself is an unacceptable “pre-exiting condition” to a healthy liberal democracy. For example, during the French presidential race, Macron’s “Ensemble, la France!” (Together, France!) strongly resembled Hillary Clinton’s “Stronger Together!” while Le Pen’s “Choisir la France!” (Choose France!) sounded similar to Donald Trump’s “America First!” Macron established himself as a pro-European centrist and environmentalist, who embraces markets, but says he believes in “collective solidarity.” His voters are more optimistic about the future, support the European Union, and embrace France’s integration with the rest of Europe and the world. Le Pen adopted the French national heroine, Joan of Arc, as her role model. This was a strategic choice, given that Joan of Arc is considered by many the “mother of the French nation,” as she was a farm girl who allegedly heard voices that told her to boot foreigners—the English—out of France, and who made the fight against the English her life mission, a mission that tragically ended with her heroic death pour la France. Metaphorically speaking, Le Pen must have been hearing the same voices – after all, she is “the heiress to a populist dynasty founded by her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, who defended torture in Algeria and called Nazi gas chambers a mere “detail” of history” (Goldhammer, 2017, May 7, para 6). Le Pen also caused controversies with her conservative views on women’s reproductive rights, her neo-colonial claims about France civilizing (formerly colonized) Algeria, her recent denial of French participation in the Holocaust, her polemics about the so-called “les Français de souche” (literally, French of strain – ethnic/native [sic] French…), and her recommendation to the French to give only “French” names to their newborn children. Like President Trump, who frequently defined German open-door immigration/refugee politics as a “disgrace” and a “disaster,” Madam Le Pen defined Macron’s policies as “mondialisation sauvage” (literally, “savage globalization”), and rhetorically located patriotism on the opposite side of the spectrum from globalization, claiming that the two concepts are mutually exclusive and thus creating a strong binary of “us” (the French) versus “them” (the threatening “sauvage” Others).

Other binaries further echoed the U.S. election race: Macron was more popular in cities; Le Pen charmed rural France. Macron appealed to middle- and upper- class voters, and was accused of being a part of the corrupt elite; Le Pen appealed to the unemployed, blue-collar workers, and farmers. Macron prioritized a stronger, united Europe; Le Pen proposed Frexit and France’s exit from NATO (an “obsolete” organization, according to President Trump). Macron criticized Russian intervention in Ukraine and Syria; Le Pen expressed admiration for Russian President Vladimir Putin. Another déjà-vu: Former U.S. President Barack Obama endorsed Macron as strongly as he had endorsed Clinton, emphasizing the salience of the French election for liberal values in Europe and the entire world, and the need to give people hope, instead of exploiting their fears. He did this in a passionate speech, to which Macron answered, “L’espoir est en marche!” (“Hope is on the move!”).

Et voilà… The election happened, and the French chose to be “stronger together.” The French President-elect chose to walk on stage at his election rally to Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” the official anthem of the EU, eschewing the traditional French La Marseillaise. Despite criticism from the opposition, the Front-National binary of patriotism versus globalization, and the skepticism of emerging Mercronism (Merkel+ Macron), Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche indeed leaves us hopeful that new forms of patriotism, and new forms of globalized togetherness and solidarity, are possible for the French, for the Europeans, and for all of us who crave an open, free, liberal world.

Online Resources

- Le Monde Diplomatique

- En Marche

- Council for European Studies

- Atlantic Council

- French-American Foundation

Media Resources: Issue Experts

- Mary Vogl, Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO

- Susana Martinez Guillem, University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM

- Karrin Anderson, Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO