What Happens When a Politician’s Images Circulate in the Media?

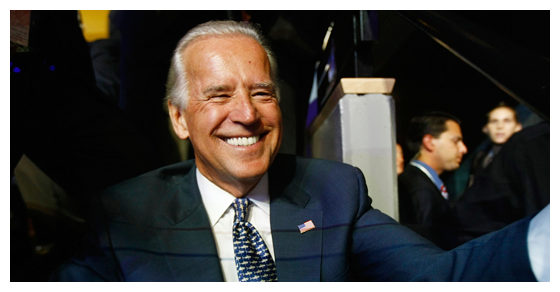

Imagine a politician’s life. You’ve just given a carefully constructed speech on a new policy, but newspaper coverage only focuses on your new haircut. You hop onto the Internet and find that there are multiple people who have started Twitter accounts on your behalf. Or, like most humans, sometimes you simply flub what you’d meant to say, as in Vice President Joe Biden’s assertion, “If we do everything right, if we do it with absolute certainty, there’s still a 30 percent chance we’re going to get it wrong.” These examples highlight some pressures that all politicians now face, as the speed and reach of new technologies multiply the potential for different perceptions about a person to circulate in public.

Since most citizens’ understandings of politics come through media, we began to wonder: When you both speak and are spoken for on so many fronts, what does it even mean to communicate an identity in this crowded, fragmented media environment? Scholars have long distinguished between a “person” (a real-life flesh and blood individual) and what’s called a “persona” (persuasive communication intended to create a certain impression about that individual by authors or audiences). A politician could give a housing policy speech full of scientific language, for instance, in an attempt to persuade others that she or he should be perceived as an “expert persona.”

Some finer distinctions have proven useful for understanding this concept’s importance. A first persona describes the role or roles individuals strategically create about themselves in their communication. Edwin Black built upon this idea by showing how communicators also try to persuade their audiences to adopt a role, or a second persona, in speech or writing. An audience listening to a presentation full of scientific language is partly being invited to approach questions of policy with a “rational, factual persona.” In turn, rhetoric scholars such as Philip Wander have showed how a third personaand similar concepts underscore the many roles communicators further exclude or reject in their messages.

With the multiplying personae made available across so many different types of media, we conducted an in-depth investigation of comedic representations about Joe Biden as a test case for understanding a politician’s intended and unintended personae. Even if Biden wants to assert a first persona of “policy expert” in public communication, for example, websites such as Tumblrand The Onion have so much satirical content about the vice president that it may be difficult for that role to ever see the light of day across media spaces. At the very least, the struggle for control of a politician’s personae is more in the hands of media producers and public audiences than ever before, complicating how invitations to audiences are made and what roles many sources include or exclude in circulating personae across the media.

Working with more than 10 years of content about Joe Biden from The Daily Show, Funny or Die, and many other programs and sites, we found media representations most centered on three personae about the vice president: a folksy guy, a gaffe machine, and a party animal. With the folksy guy persona, we found Biden not only projected this role into public culture but also had to play this role even more because of all the excess communication about it in so many different media. For example, in an appearance on The Colbert Report, Biden was asked to play up perceptions of being just a fun, average guy by dressing up in the garb of a ball park “Hot Dog Guy.”

The gaffe machine persona brought additional considerations about how advertent or inadvertent such roles may be. Biden has certainly committed many political gaffes. We found that the number of exaggerated or fake versions of gaffes attributed to Biden compounded this role further and complicated both second and third personae, especially because people are not exactly invited to become or not become “bumblers” through Biden’s, media producers’, or various audiences’ willful control.

Last, the party animal persona will be familiar to anyone who has seen photoshopped images of Biden sunbathing on the White House lawn, in a drunken stupor, or philandering around town (The Onion even has a book called The President of Vice that’s all about this persona). One Onioneditor has made clear that this brash and boozy persona isn’t intended to represent Biden whatsoever; but he also believes such images are risky because many people don’t know Biden isn’t actually like this. For our understandings of communication, fact and fiction may be less important in these circulating media representations than the associations so many of these images bring quickly to audiences’ minds. Circulating media personae come to have a life of their own, bringing pressures to any politician’s strategic efforts to fashion certain roles.

Overall, when a politician’s images circulate across many electronic platforms, producers and audiences now make persuasion about personalities a difficult undertaking. Certain political roles may also cluster across networks, as in the three distinct personae we found about Biden in our study, presenting politicians with both opportunities (e.g., to reiterate the folksy guy persona) and challenges (e.g., having to play out that role so much that other roles are constrained). In fact, important political roles may be squelched by so much media circulation. Many of the roles Biden played in 36 years in the U.S. Senate, for instance, are downplayed by the three representations we found.

Moving forward, what’s clear is that the boundaries for persuasive communication about political roles have become porous and, increasingly, every person will have to navigate the evolving nature and demands of our circulating media environment. We should be critical about the ethics and effects of these developments, as misinformation may amplify quickly. To be successful with voters, politicians will certainly need to master the task of engaging or disengaging with multiplying personae. With less of a chance to craft and control their messages, they will need be in on the joke when the circulating content is helpful while doing all possible to distance themselves from less flattering roles.